We can learn a lot about artists through their use of colour and different techniques. As an artist’s style changes, it often reflects personal life events and experiences, but did you know it can also illustrate a change in eye health?

Below we explore the work of some of the World’s most renowned artists and which sight conditions played a part in their artistic journey.

Cataract

In his 60s, Claude Monet experienced cataracts – the leading cause of blindness worldwide. Cataracts occur when the lens, the small transparent tissue inside the eye, scatters light to appear cloudy or milky to others and the optometrist as they look into your eyes and can limit or prevent vision.

When Monet noticed a change in his eyesight, he wrote to an Ophthalmologist in Paris:

“I no longer perceived colors with the same intensity… I no longer painted light with the same accuracy. Reds appeared muddy to me, pinks insipid, and the intermediate and lower tones escaped me.”

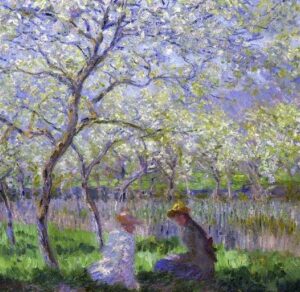

Prior to his sight loss, Monet’s paintings were full of vibrant colours and tones, with clear and sharp lines. As his vision started to deteriorate, his renderings of nature had a more abstract style, with yellow and red tones presiding over the vibrant colours used previously.

As Monet’s cataracts developed, his vision became more blurred and he struggled to identify colours in the same way. He found himself reading the labels on his paint bottles to know which colour it was.

Monet had surgery on his cataracts, which helped him to see blue and purple again. He was frustrated to find that he could no longer see yellows and reds, after the surgery. Unfortunately, in the 1900s cataract surgery was still developing and couldn’t fully restore vision.

Towards the end of his career, Monet wore tinted lenses to correct the imbalance of colour in his vision.

Retinal disease

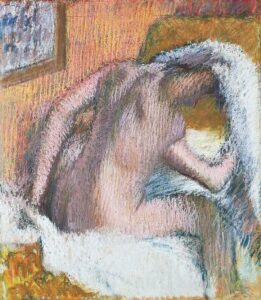

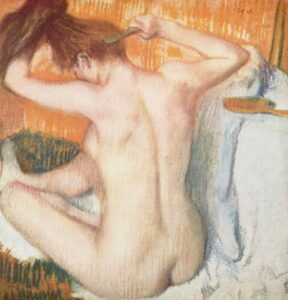

Starting to lose his sight in his 20s, Edgar Degas’ retinal disease affected his painting for the majority of his career. As he reached his 50s, he found reading challenging and by the end of his life, he found it increasingly difficult to identify shapes. But how did his sight loss manifest on the canvas?

When comparing paintings by Degas’ in his 40s to those from his 60s, the changes in shading and line definition reflect the changes in his vision, but the changes in subject matter reflect the changes in his mind.

When Degas lost sight in one of his eyes and meeting with eye health specialists, his art began to reflect his interest in subjects related to sight. Many of his works featured people using glasses, with a series of artwork featuring a woman holding opera glasses.

How Edgar Degas adapted his techniques as his sight deteriorated

As he lost sight in one eye, Degas developed a range of methods to allow him to paint effectively. These included using head movements and touch to establish dimensions, and studying his subjects from a multitude of angles to capture more detail.

An example of how his changing vision affected his artistic style, is the comparison of two paintings from 1886 and 1905. The difference in detail and colour offer an insight into how his perception of his models changed. The 1886 painting below uses bold colours and clean line work, whereas the 1905 artwork uses a darker blend of colours and an abstract rendering of the subject.

Like Monet, Degas’ work was inspired by his visual perception of his subjects. As his sight deteriorated further, it is likely Degas would have also used bottled paint to identify colour. It is thought that in his later career, Degas even asked his models to identify the colour of paint that he was using.

Strabismus

In 2004, two neurologists from Harvard University highlighted that Rembrandt’s eyes were misaligned in his self-portraits. One eye would be forward-facing, but the other would be facing a different angle. After considering a range of his self-portraits, they found it was highly likely that he had strabismus.

A key sign of strabismus includes the eyes pointing in different directions, which can cause double vision, lazy eye and poor depth perception. It is theorised that Rembrandt closed one eye when painting to avoid double vision affecting his work.

Similarly, Leonardo Da Vinci is thought to have had a sight condition called intermittent exotropia, which can cause one or both eyes to face outward. It affects around one in 200 people.

As with Rembrandt, researchers analysed Da Vinci’s face from paintings, drawings and sculptures and determined that he may have had strabismus. They also suggested that the condition could have been beneficial to his work, as it would have allowed him to switch to monocular vision (using both eyes separately) so he could focus on flat surfaces in close range.

Creating art with sight loss today

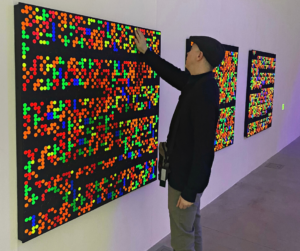

Following in the footsteps of these incredible visually impaired artists, creatives living with and facing sight loss continue to adapt art around their sight conditions. Clarke Reynolds, also known as the Blind Braille Artist is one of the modern-day trailblazers in accessible art.

Clarke is best known for his thoughtful and vibrant braille art, where he uses the tactile language of raised dots to recount his journey as an artist, as well as convey a unique insight into the lived experience of blind and partially sighted people. Clarke’s recent exhibitions have been hosted at prestigious galleries including Quantus Gallery in London and Aspex Portsmouth.

Please DO touch…

Clarke has long insisted his art is accessible to everybody. His braille pieces are surrounded by signs reading “Please DO touch”, encouraging children and adults alike to interact with them.

“I hope my exhibition can help to change people’s attitudes of the possibilities of what blind people can achieve. I want to shake up the stereotypical attitude out there towards sight loss and use my work to improve the knowledge about blindness and hopefully how blind people are treated. We are strong, capable, creative and want the sighted to open their eyes to our see this” says Clarke.

Inspiring the next generation of creatives

Vision Foundation has funded projects that transform the lives of blind and partially sighted people for over 100 years. From touch tours and audio described theatre performances, to dance classes and music lessons. Find out more about the work we support here >